From her arrival, Schafer kept a diary, a record of what she has seen and felt as a humanitarian worker in a profoundly damaged nation.

It is a portrait of life and death in the time of Ebola, describing the strangeness of not being able to hug old friends and the pain of a colleague who was not allowed to be with his daughter as she died; the struggle to equip teachers with skills that will be needed to deal with grief-stricken children when they return to school; and the determination of a fellow aid worker to save a stray dog in a country engulfed by sadness and death.

On January 21, in Kono, a district once so rich with diamonds that people said you could pick them up on the road but now desperately poor and fearful of the disease, Schafer talks to children separated from Ebola-infected parents. The following night, walking along a beach in the capital, Freetown, she suddenly bursts into tears, fearing for what will become of the children she has met and questioning how she can help.

“Tonight, as I walked along the beach, I got halfway back to my hotel and burst into tears. I couldn’t help but wonder what hope an eight-month-old orphan in Sierra Leone has for a good and prosperous life. And how will that adorable 14-year-old girl readjust to life without her father? Will she be forced to not return to school so she can help bring in family income? How can I make things better here?”

On February 4, in the city of Bo, Schafer meets a man working at an interim care centre for children orphaned by Ebola. He tells her he is the only survivor in his family and that his wife and children have died in the epidemic.

“He said, ‘When I look at these children every day, I’m reminded of my own children who are not here any more.’ He broke down and wept. And wept some more. This man who has lost his children said that this work was the only thing that truly made him feel life was still worth living — that he could help other children when he couldn’t help his own.”

In Bo, on March 14, Schafer watches as one of World Vision’s burial teams performs what is referred to as a “safe and dignified” burial of a woman suspected of dying from the disease. These teams, she writes, are “true heroes” in the fight against the epidemic. But they have paid a heavy price, with many of them ostracised by their communities.

“Yesterday was particularly sobering — and quite challenging. I was asked, while I was in Bo, to meet our safe and dignified burial team. Staff in Freetown and management felt they might benefit from some simple stress management training. So I went to see them and observe their work.

“World Vision and the Red Cross are the two main organisations working with the Ministry of Health and Sanitation to undertake the safe and dignified burial of people who have died from Ebola, are suspected to have died from Ebola or who died from unknown causes (which could be Ebola). They’ve been employed because Ebola is still viral and contagious even after a person has died. Therefore, the traditions of washing bodies, dressing them and carrying them to a gravesite were some of the major causes of the spreading Ebola infection.”

Schafer describes how the teams meet each day at 6.30am at the local football oval and travel to the dead in three vehicles, with members of the team given the tasks of “community engagement”, or to “interact” with the body, or to transport it.

In Bo, she watches the way the team engages with the children and husband of the 56-year-old woman who has died. She writes that they were “beautiful to watch in their conversation” with the family, supportive even as they logged the location of the death on a GPS and recorded the names of those who were in contact with the dead. A crowd gathers around the house. “Some were crying. Some showed curiosity. I saw a child showing fear. It’s strange and abnormal for three vehicles to come when someone dies. And by now the whole nation knows why they’re there.”

One of the burial team members speaks to the crowd, “loud enough for people to hear, but in a gentle tone”. He says it is not certain the woman has died from Ebola and describes what will happen: because the deceased is a woman, a female member of the burial team will enter the house wearing full protective equipment and dress the woman for her grave; another team member will then take a swab from the body (demonstrating how they will open her mouth); and two men will place the woman in a bag so that there is no risk of contagion.

The body is brought out in a white body bag on a stretcher and driven to the mosque, where only 10 people are allowed in for prayer, and then to a local cemetery. Women are wailing, men fight back tears as they follow from a distance. “In the ground, a rough-edged wooden stake with the number 2195 was placed at the head of the grave,” Schafer writes. “This is how they will know her in the Ebola records.”

At a new cemetery, already almost full, World Vision has begun placing the names, ages and faiths of the dead on name plates alongside the wooden stakes, “to ensure those that have died are remembered by more than just a number”.

“The burial teams do this anywhere between four and 12 times a day. They have buried men, women, girls, boys and infants. They have sometimes removed multiple family members from the one household. And every day they deal with people who are mourning, in shock, bereaved, confused, sometimes angry, sad.

“These men and women are surely doing one of the hardest jobs in this Ebola response. But sadly, when I spoke with the team members — about 60 of them in total back at their ‘oval’ — their challenges are much greater than just the job itself (as if this weren’t hard enough).

“Many of them had been driven out of their family homes and communities because they are working in the safe and dignified burial teams and people are frightened they may be infectious. When I asked for a show of hands of how many this had happened to, easily three-quarters raised their hands. Some of these people were having to find new accommodations, being charged higher rents because landlords see them as having cash for working for an NGO and a few reported actually sleeping in the rafters of the oval where they meet each day before going out to the sites.

“Most of them reported being anxious about what happens after their contracts end because they believe they will no longer be employed in their communities.

“People fear them. They fear they are carrying the disease because they are burying people who have had the disease. They also think that their work is bad luck on the family, so they want to keep their distance.”

Reports abound, Schafer writes, of members of burial teams not being served in shops and, in one instance, being refused entry to a mosque for prayer.

In a recent diary entry, Schafer writes of returning to Freetown from a village near Bo. “As we drove back to town, one of Sierra Leone’s brightly coloured and intricately painted trucks was hurtling towards us. As we, and the truck, slowed down to pass each other, I read a message on the truck that said: ‘No condition is permanent’.”

It is an idea that gives her only a little comfort. In an impoverished country that already had one of the highest infant mortality rates, with more than 15 per cent of children dying before their fifth birthday, many thousands of children have lost one or both parents to Ebola. The Sierra Leone government estimates 8360 of its children have lost at least one parent. The World Bank estimates, more conservatively, that 9600 children across the three affected West African countries have lost at least one parent and 600 children have lost both parents.

Ebola also has spawned a social epidemic, with marked increases in early marriages, teenage pregnancies, child labour and sexual abuse.

About 2.5 million people are considered likely to need food support in the next year.

“Sierra Leone and its people will work towards zero Ebola cases now while the search for better treatments and maybe even a vaccine continues. Eventually, all orphaned children will be placed in homes and schools will eventually function again.

“The health systems will slowly be strengthened and, given time, livelihoods will be restored. Certainly, the grief will likely lessen today compared with yesterday. Many things will improve.

“However, if children are not supported now, the impacts may indeed be permanent. Now is the time for action, not just in the past and not just to save lives, but now is our chance to save the quality and dignity of lives left behind.”

She ends the entry: “I know I won’t forget the children I’ve met. The eight-month-old girl who no longer has a mother and father. The 15-year-old girl who lost her father and misses him. The man who lost his wife and children and was left the sole survivor of his family. My colleague and his pain at not being able to even see his daughter before she died. The burial team members and their respect for all those they are putting in the ground and the work they do despite the awful treatment they receive. And the 16-year-old girl I met this week who now, without a mother, is potentially going to be married off just so she can survive.

“Ebola itself may be on the decline, but the recovery concerns, the challenges and the battle will continue here in Sierra Leone. I desperately hope they won’t have to do it alone, without the care, concern and support of the rest of the world.”

Last month Sierra Leone’s President, Ernest Koroma, ordered a three-day national lockdown, instructing the country’s six million people to stay in their homes from March 27 to 29 in a bid to achieve a zero spread of Ebola by the beginning of the rainy season.

“The economic development of our country and the lives of our people continue to be threatened by the ongoing presence of Ebola in Sierra Leone,” Koroma said.

This week, almost two million children returned to school in Sierra Leone. Schafer has been closely involved, co-writing a national training manual for the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology to help teachers recognise and deal with signs of trauma in a nation of children whose lives have been profoundly disrupted.

“Although they may be concerned about the possibility of catching Ebola in the classroom, they are more worried that they’ve forgotten everything they’ve learned,” she says. “They’re anxious about whether they can ever catch up.” The government has waived school fees for all children for the next two years to encourage enrolment.

Stuart Rintoul is senior media officer (emergencies) for World Vision Australia.

Link to original article in The Australian

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'

ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'  "These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein

"These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein  How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.

How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.  What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on

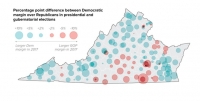

What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto

On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in

A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen

In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed

Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed