The recent outbreak of the Ebola virus epidemic in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone has exposed the underbelly of many of Africa’s healthcare systems. They are often poorly funded, severely neglected and in some cases virtually nonexistent. The disease’s virulence has overwhelmed health systems that even before Ebola lacked basic equipment and facilities, medical staff and supporting infrastructure.

Ebola has shaken and awakened decision-makers in a way that malaria, tuberculosis and other epidemic diseases that claim millions of lives in Africa each year have failed to do, with the possible exception of HIV/AIDS.

As fate would have it, the epicenter of the virus is in countries that are among the world’s poorest, although in 2013 Sierra Leone and Liberia ranked second and sixth among the top 10 countries with the highest economic growth rates in the world, according to The Brookings Institution, a US think tank. As reported by The New York Times, “The disintegration of the health care systems in the affected countries is already having a profound impact on the populations’ health beyond Ebola, as clinics close or become overwhelmed or nonfunctional.” To exacerbate the situation, these health systems, including the general infrastructure, were wrecked by internal conflicts and civil wars to the point where they now struggle to provide basic health care to citizens.

A wake-up call

Although the years of conflicts in West Africa are still being felt, this does not solely explain the devastation brought by the Ebola virus. Graça Machel, the widow of former South African President Nelson Mandela, said the Ebola outbreak should be a wake-up call for African leaders. “Ebola has exposed the extreme weaknesses of our institutions as governments, countries which are affected were found totally unprepared,” she told African business leaders in November 2014 at a meeting in South Africa.

The prognosis for the affected countries, which now include Mali, is even more dire. In an editorial in The New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Jeremy J. Farrar of the Wellcome Trust, a charity that funds research in health, and Dr. Peter Piot of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who helped discover the Ebola virus in 1976, write: “West Africa will see much more suffering and many more deaths during childbirth and from malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, enteric and respiratory illnesses, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and mental health during and after the Ebola epidemic.” They warn of “a very real danger of a complete breakdown in civic society, as desperate communities understandably lose faith in the established systems,” adding that “without a more effective, all-out effort, Ebola could become endemic in West Africa, which could, in turn, become a reservoir for the virus’s spread to other parts of Africa and beyond.”

Back in 2001, African health ministers signed on to the Abuja Declaration pledging to allocate at least 15% of their national budgets towards improving their health systems. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a decade after the declaration was signed, 27 countries had increased the proportion of their total government expenditures allocated to health, but only Rwanda and South Africa had achieved the 15% target. More depressingly, seven countries had actually reduced their health budget over the same period, and 12 had not made any progress. A different scorecard developed by the Africa Health, Human & Social Development Information Services (Afri-Dev.Info), a research coalition, showed that by 2010, the top five countries who had met the target were Rwanda (23.3%), Malawi (18.5%), Zambia (16%), Burkina Faso (15.7) and Togo (15.4%).

In 2013, Africa had an estimated deficit of 1.8 million health workers. Perhaps not surprising is the state of the health systems in the affected countries. According to Afri-Dev.Info, in 2014, with a population of 4.2 million, Liberia had only 51 doctors, 269 pharmacists, 978 nurses and midwives, while Sierra Leone, with 6 million people, had 136 doctors, 114 pharmacists and 1,017 nurses and midwives.

Slow global response

Regrettably, Ebola struck at countries whose health systems were already on their knees. This has not stopped analysts from acknowledging that the response to the outbreak was indeed weak. Politico, a US publication, wrote: “The response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa will never be remembered as an example of good leadership. Not by the governments of the countries involved, not by other nations, and not by the international health organization that says it’s there to deal with public health emergencies.”

True, the world was found wanting in its response to the Ebola epidemic, but it has been the World Health Organization, the main UN health arm, that has borne the brunt of the criticism. It was faulted for taking too long to declare the outbreak an international emergency. Indeed, it was not until August that it declared Ebola an emergency, and by that time the disease was already ravaging the affected areas. “Hindsight is always better,” said Dr. Margaret Chan, the head of WHO. “All the agencies I talked to — including the governments — all of us underestimated this unprecedented, unusual outbreak.”

To be fair, WHO has suffered from severe funding cuts in recent years. Its two-year budget for 2014-2015 is about $4 billion, having been cut by $1 billion in 2011, according to reports. This has crippled its effectiveness in handling global health emergencies. The New York Times reported that WHO’s “outbreak and emergency response units have been slashed, veterans who led previous fights against Ebola and other diseases have left, and scores of positions have been eliminated — precisely the kind of people and efforts that might have helped blunt the outbreak in West Africa before it ballooned into the worst Ebola epidemic ever recorded.” Notwithstanding, global health experts say that even if WHO had had better funding, it is neither an emergency-response network nor a direct provider of health care services, but a technical agency that provides advice and support.

The affected countries too have to shoulder some of the criticism. They waited until it was too late to request international aid. When governments are reluctant to ask for help, Sophie Delaunay, the executive director of Doctors Without Borders, told Politico, “they become responsible when the situation deteriorates.” There are, however, reasons why countries are not quick to request help or try to suppress bad news. In many cases these have to do with national pride and the fear of scaring away tourists and investors. And these fears are not unfounded. African tourism has borne the brunt of the Ebola fear factor. Francisco Ferreira, the World Bank’s chief economist for Africa, said the Ebola “fear factor” prevents tourists from visiting even countries such as Kenya and South Africa where there had been no cases of the virus.

Stigmatization

In addition to the economic, social and political impact of Ebola is the stigma attached to it. Nigeria’s finance minister, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, cautioned against lumping all African countries together to avoid hurting the economies of non-Ebola countries. “If you scare away investors by lumping the continent into one big mass, what good does it do? It will take another decade to recover.”

Politicians around the world have sounded the same warning, worried that Ebola was creating a contagion effect on African economies. “We have to isolate the disease, not the countries affected,” said UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.

Vaccines and profits

The absence of any drugs or vaccines against the scourge of Ebola has been the main source of fear among the public. According to Time, a US weekly magazine, the scarcity of drugs and vaccines is not due to a lack of innovation. “Drugs have been in development for years, but since pharmaceutical companies have had no financial incentive to fund them, researchers have hit walls.”

Dr. Chan makes the same point, adding that the drug industry’s drive for profit was one of the reasons there has been no cure yet for Ebola. “A profit-driven industry does not invest in products for markets that cannot pay,” she told delegates at a conference in Cotonou, Benin. Testing on healthy volunteers in the US and some African countries has started on experimental vaccines and results are expected during the first quarter of 2015.

The time will come when the decision-makers will take stock of the state of healthcare systems in many African countries, how the outbreak unravelled and the effectiveness of the global response. Nevertheless, even as the epidemic is stabilizing in some parts of the affected countries, it’s spreading in others, especially Sierra Leone, and to a lesser extent Mali. “Now is no time to let down our guard,” warned the UN Secretary-General. “A gap anywhere in the response leaves space for the virus to spread disease, kill people, destroy families and threaten the world…We must keep fighting the fire until the last ember is out.”

- See more at: http://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2014/ebola-wake-call-leaders#sthash.DjAobHg6.dpuf

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'

ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'  "These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein

"These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein  How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.

How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.  What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on

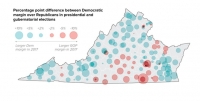

What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto

On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in

A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen

In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed

Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed