But rainfall has been decreasing in the northwestern Turkana region of Kenya for decades. Droughts now drag on interminably; one a quarter-century ago wiped out his goat herd. Rivers that once supplied drinking water have run dry.

As the world grows increasingly concerned about the looming effects of climate change, the perils are already visible in African regions such as this one.

Temperatures have risen by at least 0.5 degrees Celsius — that’s nearly 1 degree Fahrenheit — in the past 50 to 100 years in most parts of Africa, and they are projected to rise faster than the global average in the 21st century, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the leading international authority on the subject. Most scientists say this increase is because of man-made greenhouse-gas emissions.

Turkana has long suffered from cyclical drought, and the lake’s levels have risen and fallen over the years. But the increasingly erratic rainfall pattern hews to scientific predictions about the effects of climate change.

Scientists think the warming will probably continue even if the world makes good on the commitments reached last month in Paris in a landmark treaty to lower greenhouse-gas emissions.

In Africa, the effects of rising temperatures could be especially dramatic. By mid-century, climate change will probably reduce the yields of major cereal crops in sub-Saharan Africa by more than 20 percent, according to the IPCC.

“Africa is projected as the continent that will experience climate deviations earlier and more severely than any other region,” said Richard Munang, coordinator of the Africa Regional Climate Change Program for the U.N. Environment Program.

A variety of factors make the continent especially vulnerable. Africa is naturally subject to extreme weather, and two-thirds of the continent is already made up of desert or drylands. Africans depend heavily on natural resources — rain-fed agriculture employs 70 percent of the population, according to the World Bank. Many countries are too poor to afford projects to help residents cope with the change, such as sophisticated irrigation systems.

The impact of the warming will vary. In some areas, droughts will extend; in others, there will be flooding caused by rising sea levels as glaciers melt or seawater expands because of higher temperatures, scientists say.

“I don’t know what climate change is, but I know from all the changes — the constant droughts, the seasons are gone — these are changes happening in our land. Our life is becoming hard, and we can’t do anything,” said Tioko’s 60-year-old father-in-law, Joseph Ekimomor.

Turkana is known as the “cradle of mankind,” because its soil holds the richest fossil record of human origins ever found.

Tioko lives in Namakat, a village of acorn-shaped huts. Two decades ago, he had 200 goats and two camels. He married three women, a sign of prosperity in Turkana culture.

But the region was already drying out. From 1940 until this year, rainfall has decreased by 25 percent in Turkana while temperatures have risen steadily, according to research by Chris Funk, a geographer at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Kenyan government figures obtained by Human Rights Watch show temperatures in Turkana increased by between 3.6 and 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit between 1967 and 2012.

“We always used to have droughts, but they didn’t finish everything. I’d remain with at least five goats, and then I could start over again, but then there was the drought that finished everything,” Tioko said.

He does not remember when that occurred, but it was probably the drought in 1991-1992 that affected 1.5 million Kenyans. He now survives by fishing.

Climate change is exacerbating the droughts: Warming temperatures reduced the April-to-June rainfall in East Africa in 2014 by 11 percent, according to research by Funk.

Tioko’s wife, Elizabeth Lomare, kneeled along open coals under Turkana’s sweltering midday sun one recent day. She swirled five palm-sized Nile perch in water in an aluminum pot for herself and her nine children. Tioko had gotten lucky with fishing, providing their first meal in two days.

Her children dashed in and out of huts woven from palm fronds. Most were home on a weekday because there are no schools nearby. Her two oldest children walk several hours to high school, but without money for books or a uniform, they are unsure if they will be able to stay enrolled.

The children’s hair was the color of polished pennies, their teeth the color of amber. One child, a 7-year-old, limped because he has developed bowlegs. Such irregularities are related to Lake Turkana’s high fluoride levels, which are caused by past volcanic activity, according to researchers.

Lomare knows the kids should not drink from the lake, but the seasonal rivers where she used to collect water have dried up. When there is money, she walks two hours to the nearest town to buy water.

“The difference between life and death for the Turkana people is just so fine, and this is putting them over that balance,” said Felix Horne, a Human Rights Watch researcher who has studied Turkana.

After the last of his goats died, Tioko moved his family closer to the lake so he could at least fish for food. His father-in-law and mother-in-law, Leah Nakadi, 58, followed. But the supply of fish has dwindled, in part because of decreasing water levels.

The situation in the region is expected to worsen — and not just because of climate change. Ethiopia recently completed the Gibe III dam, which hydrologists say will choke Ethiopia’s Omo River Basin, the source of more than 90 percent of Lake Turkana’s water.

“With my age, I’m just counting the days. I’ll die anytime, but what of my grandchildren? I want them to have a future, but what are their lives going to be?” Ekimomor asked.

“Maybe God knows how we’ll survive,” his wife added.

Link to original article from The Washington Post

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'

ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'  "These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein

"These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein  How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.

How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.  What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on

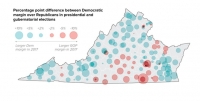

What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto

On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in

A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen

In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed

Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed