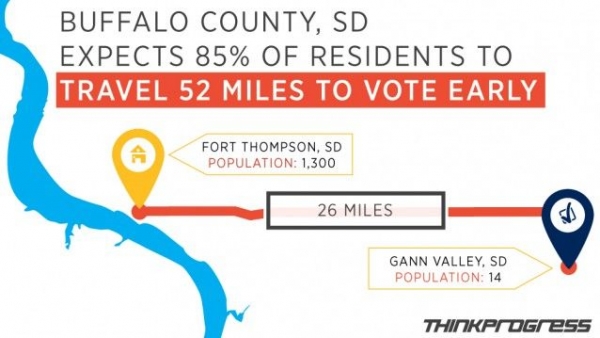

While South Dakotans across the state have been voting for weeks — the state offers 46 days of early absentee voting — the Crow Creek Sioux have yet to see their ballots. The closest early voting site is a 50 mile roundtrip away in Gann Valley, a town with a population of 14. The Buffalo County auditor, a white resident of the town, has refused to set aside federal funds to open a satellite office for early voting on the reservation this year.

That 50-mile trip is effectively impossible for many people on the reservation. Sixty-five-year-old Crow Creek resident Sylvia Walters lives in a government-subsidized apartment building for the elderly and disabled in Fort Thompson, the largest town on Crow Creek. She told ThinkProgress that because she doesn’t have a car, she has to pay someone to drive her if she wants to leave her immediate part of town. “I stay home a lot. Let’s put it that way,” she said. Although she plans on voting in November, she said she would have preferred having the option to vote early. “Sometimes you forget on the day or you’re busy,” she said. “This way when you’re thinking about it you can get it done.”

Native American voting rights group Four Directions has been fighting since 2002 to give Indians the same voting opportunities as other South Dakotans. Over breakfast at the Lode Star Casino in Fort Thompson, executive director OJ Semans, his wife Barb and Buffalo County Commissioner Donita Laudner told ThinkProgress the county’s refusal to open an early voting center is an attempt to suppress Native American votes.

“You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to know that if you’re given 46 days to vote, you are going to have more people vote than if you’re given one day,” Semans, a Rosebud Sioux, said. “[The auditor] says there’s six different ways to vote, but we don’t want six different ways. We just want what you have, which is a satellite office.”

The reservation crosses three counties, with a majority of the 2,000 Crow Creek Sioux tribal members living in Buffalo County and making up 85 percent of the county’s population. Twenty-six miles east, the 14 people who live in Gann Valley form the smallest county seat in the country — and Semans said last time he checked, someone had crossed off 14 on the population sign and wrote 11 in marker.

Without a local polling place, the residents of the Crow Creek reservation will either have to travel the 30 minutes to Gann Valley to take advantage of early voting or wait to vote at the polling place that will operate at the reservation’s Catholic church on Election Day. With most of the reservation living below the poverty line and no public transportation in the area, the 26 mile distance can be enough to prevent much of the population from voting.

“They may have a vehicle, but the vehicle may not have a license on it or they may not have insurance,” Laudner said. “And have you seen our gas prices? People don’t venture off.”

Greg Lembrich, a New York attorney who also serves as legal director of Four Directions, told ThinkProgress that driving an hour to vote early is not an option when people are living in deep poverty. “Given the transportation difficulties, the levels of poverty, the rural nature, the distance between communities, the more time people have to get the polls, it becomes much more likely that we’re going to get them to participate and cast their ballots,” he said.

The federal government passed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) in 2002 to provide funding for states to meet minimum election standards. Elaine Wulff, the county auditor, told ThinkProgress that Buffalo County has HAVA funds available, but they are not replaceable once they are used. “It’s a limited supply and they won’t last very long,” she said, but then added the county was reimbursed after the 2012 election. “If we used this money for an early voting center, it would take away from the Buffalo County budget funds.”

Laudner estimates the office would cost the county approximately $5,000 and the money would be reimbursed from the state’s HAVA fund of more than $9 million in interest-bearing accounts.

South Dakota’s 2014 HAVA plan specifically states that funds can be used to set up an additional in-person satellite absentee voting location if the particular jurisdiction has 50 percent more individuals below the poverty line than the rest of the county, and if the residents live 50 percent farther from the county seat than the rest of the county — both conditions that Fort Thompson meets.

During a state Board of Elections meeting in July 2013, Four Directions requested that South Dakota use HAVA funds for satellite voting centers on three Sioux reservations. Secretary of State Jason Gant (R) said he’d ask the federal Election Assistance Commission for permission. But Stephanie Woodward, a journalist covering Native American issues, reported at the time that Gant knew the request would not be answered because the EAC didn’t have staff to respond to such a query.

Donita Laudner represents the Crow Creek Sioux reservation as a Buffalo County Commissioner.

CREDIT: KIRA LERNER

When Laudner questioned the lack of a satellite office at this month’s Buffalo County Commissioners meeting, she said she was told that Wulff didn’t want to expend the HAVA funds because they would run out. However, “if they spend the money, they get it back,” Laudner pointed out. “A measly $5,000 for early voting is not going to break you.”

The county is refusing to designate HAVA funds because they’d rather use the money for other purposes, Lembrich said. “Which really begs the question: what other things? The funds are to help Americans vote and the Americans in Buffalo County that need help voting are the 1,300 Native American residents who live and around Fort Thompson, not the 14 people in Gann Valley who can walk across the street any day of the week and vote.”

Four Directions has fought for and won early voting centers on other reservations across the site in past election cycles, including Buffalo County in 2012. As a result of early voting in Fort Thompson, Native American voter turnout rose from 55 percent in 2008 to nearly 75 percent in 2012, the largest increase among the state’s 66 counties.

“While voting on the rest of the state has gone down, voting on tribal communities and the reservations has actually gone up,” Lembrich said.

Looking to continue its successful efforts before the midterm election this year, Four Directions filed a lawsuit this month on behalf of four Native Americans in the western Jackson County, South Dakota, home of the Oglala Sioux tribe, alleging that the lack of a satellite polling center on the reservation prevented Native Americans from voting. The suit claimed that Indian citizens in Jackson County have to travel almost two hours on average — twice as long as the round-trip travel time required for white citizens — to reach their polling location.

http://thinkprogress.org/wp-content/themes/tp4/images/pullquote-icon.png) 0.7em 50% no-repeat;">While voting on the rest of the state has gone down, voting on tribal communities and the reservations has actually gone up.

Last week, Jackson County agreed to the Native Americans’ request for a preliminary injunctionand opened an early voting polling center on the tribe in Wanblee, Jackson County on October 20 for both voter registration and early voting.

“Previously the early voting was available only at the county seat in Kadoka, which is 90 percent white and not on the reservation,” Eileen O’Connor, an attorney with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, who represented the Jackson County Native Americans in the litigation, told ThinkProgress.

At this point, all of the counties Four Directions has worked with have early voting sites except Buffalo County, where much of their get out the vote effort is now focused.

Both Laudner and Semans know the power of the Native American vote. Laudner led Senator Tim Johnson’s Buffalo County office during his 2002 campaign while Semans’ wife led the office in her county. When Johnson won by just 524 votes, many South Dakotans blamed the Native Americans for “stealing the vote,” Laudner said.

“We’re such a small, minute number. But that small, minute number is going to make it and push them over,” Laudner said.But while progress is being made across the state by Four Directions and other Native vote advocates, Buffalo County has regressed. Like Walters, other elderly and disabled Crow Creek residents said it would be difficult or impossible for them to travel to Gann Valley to vote.

Joy White Mouse has been in a wheelchair for much of her life since she suffered serious injuries in a car accident. She also lives in Fort Thompson’s subsidized housing and requires constant care from her children and other aides.

Laudner is working to certify tribal members as notaries so people can vote absentee, but if White Mouse isn’t able to vote by mail, she’ll have to have assistance to get her wheelchair down the road to the polling center or to the notary’s office– a difficult task in a town without sidewalks and with unevenly paved roads. Even if she could drive to Gann Valley, the polling center isn’t wheelchair accessible.

Semans said it’s too late for the county to open an early voting center in Fort Thompson for the midterms, so Four Directions and Laudner will focus on get out the vote efforts before election day.

“I have no doubt in my mind that the only reason the county isn’t setting up a satellite office out here is because they are Native American Indians,” Semans said.

The county’s unequal treatment of Native Americans extends beyond early voting– as a commissioner, Laudner said she represents close to 1,000 Buffalo County residents while the two other commissioners each represent fewer than 200 people. That’s why she became involved in the county government and Native votings rights efforts– to fight to equalize their voting opportunities.

“Whatever happened to one man, one vote?”

Link to original article from ThinkProgress

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'

ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'  "These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein

"These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein  How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.

How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.  What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on

What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto

On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in

A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen

In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed

Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed