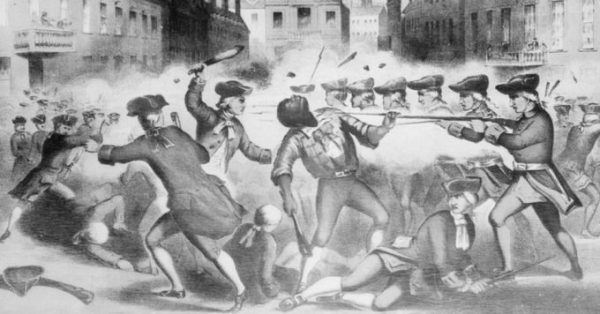

On that cold day, people had had enough. Word spread after a British private beat a young man with the butt of his musket. By late day, hundreds of Bostonians gathered, jeering the small crowd of redcoat soldiers arrayed with muskets loaded. The soldiers fired into the crowd, instantly killing Crispus Attucks and two others. Attucks was a man of African and Native American ancestry, and is considered the first casualty of the American Revolution. It took the indiscriminate murder of a man of color, by armed agents of the state, to launch the revolution. Which brings us to Ferguson, Missouri.

“Nearly seven months have passed since the shooting death of 18-year-old Michael Brown,” U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said in opening his press briefing Wednesday. He was detailing the findings of two Justice Department investigations in the killing of the unarmed African-American youth by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson. “The facts do not support the filing of criminal charges against Officer Darren Wilson in this case. Michael Brown’s death, though a tragedy, did not involve prosecutable conduct on the part of Officer Wilson.” With those words, the outgoing attorney general laid to rest any prospect of a criminal trial sought by so many seeking justice for Michael Brown. But Brown’s death continues to send shock waves, through his community, and beyond.

Importantly, Holder went on to describe the findings of the second, broader study, titled “Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department.” “Local authorities consistently approached law enforcement not as a means for protecting public safety, but as a way to generate revenue,” he reported. Ferguson, he said, was a “community where both policing and municipal-court practices were found to disproportionately harm African-American residents ... this harm frequently appears to stem, at least in part, from racial bias—both implicit and explicit.” Ferguson is one of about 90 municipalities in St. Louis County, in the suburbs of the city of St. Louis. Ferguson and many other towns in the region generate a significant portion of their annual budget by heavily ticketing people for minor infractions.

“Despite making up 67 percent of the population,” the DOJ report stated, “African Americans accounted for 85 percent of FPD’s [Ferguson Police Department] traffic stops, 90 percent of FPD’s citations, and 93 percent of FPD’s arrests from 2012 to 2014.” Michael-John Voss, managing attorney at ArchCity Defenders, represents many of those harassed by these police stops. He told me, “What we have in St. Louis, in the municipalities in St. Louis County, is a modern debtors’ prison. African-American are disproportionately targeted by police ... they are also exploited because of their financial inability to pay certain fines and costs related to that traffic stop. If they don’t have the ability to pay, they become incarcerated.” The fines mount, creating a vicious cycle, leaving the predominantly poor African-American victims trapped by debt.

The 100-page DOJ report includes numerous, disturbing cases of racist Ferguson police conduct, from use of the N-word during violent arrests to emails with comments about President Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama. One email depicted him as a chimpanzee; another predicted he would not last as president because “what black man holds a steady job for four years.” Further email exchanges revealed the extent to which revenues from infractions were actively pursued by city government. In one email, Ferguson Police Chief Tom Jackson bragged “of the 80 St. Louis County Municipal Courts reporting revenue, only 8, including Ferguson, have collections greater than one million dollars.”

Eric Holder, giving what could ultimately be his final press briefing before stepping down (depending on if and when the Republican majority in the Senate approves his nominated successor, Loretta Lynch, who would be the first African-American woman to serve as attorney general), announced that Ferguson and surrounding communities will be under federal supervision. They will change, or the Department of Justice will sue them to force change.

“It’s not about making minor reforms and plotting along in the same direction,” Ohio State University law professor Michelle Alexander, author of “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” told us on the “Democracy Now!” news hour. “It’s about mustering the courage to have a major reassessment of where we are as America, reckon with our racial history as well as our present, and build a broad-based movement rooted in the awareness of the dignity and humanity of us all.”

From Crispus Attucks to Michael Brown 245 years later, two things remain clear: We never know what sparks a revolution. And black lives matter.

Denis Moynihan contributed research to this column.

Link to original article from Common Dreams

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'

ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'  "These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein

"These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein  How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.

How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.  What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on

What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto

On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in

A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen

In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed

Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed