In late October, a few days after local news cameras swarmed Detroit’s courthouse to hear closing arguments in the city’s historic bankruptcy trial, “Commander” Dale Brown cruised through the stately Detroit neighborhood of Palmer Woods in a Hummer emblazoned with the silver, interlocking-crescent-moon logo of his private security company.

Brown rolled down the window to ask a middle-aged woman walking her dog whether everything was okay (it was), and whether she had seen anything out of the ordinary (she hadn’t). Satisfied, he continued on, guided by a futuristic tablet map of the neighborhood’s languid streets. These had become even more impenetrable last year when the bankrupt city paid for and constructed a series of traffic barriers on the community’s edges. On his right, he pointed out, was the Bishop’s Residence, a 30-room Tudor Revival castle originally commissioned by a family of fabulously wealthy automobile pioneers who later sold their company to General Motors.

“This is the part of Detroit that most people are not aware of,” Brown told filmmaker Messiah Rhodes and me. And indeed, the turreted neighborhood did look far more like something you would find in Detroit’s mostly white suburbs than deep inside the city itself.

Brown is the founder of Threat Management, a private security company hired by the Palmer Woods’ neighborhood association to provide 24-hour protection to this elite enclave. He knows the two sides of Detroit more intimately than just about any of its residents. After a stint as an Army paratrooper, he moved to the city’s East Side in the mid-1990s and into a neighborhood dubbed “crack alley.” There, he started running free security for his neighbors and a few adjacent apartment buildings with only a rifle, a dog, and psychological tricks like heavily pocketed vests, since “pockets represent the unknown.” Next, he worked at a nightclub, enforcing such a strict no-beating-women-on-the-dance-floor policy that the joint soon had a regular stiletto-heeled line out the door.

Two decades later, Brown’s officers, with their distinctly paramilitary aesthetic, are among the most recognizable of a burgeoning number of private security personnel and surveillance systems scattered across neighborhoods in the former Motor City that people with money have decided are worth protecting.

But the future of the rest of the sprawling city—once the symbol of American industrialization and working-class power—remains at best insecure, physically and financially. In the 1940s, President Franklin Roosevelt declared Detroit, then the nation’s fourth largest city, the “great arsenal of democracy” for churning out bombers for the Allied powers, as in peacetime it rolled out cars for the consumer economy. Then the auto giants began closing their urban factories and reopening their plants in white suburbs. In the same era, the industry, national unions, and the FBI all cracked down on the labor organizations founded by radical black workers.

The foreclosure crisis of this century, fueled by racially discriminatory predatory lending, forced hundreds of thousands of residents out of the city. The governor’s office placed the public school system and then the entire local government under emergency management, suspending the democratic process in the “arsenal of democracy.” And now, after seven decades of these slow-moving storms, including acts that are almost impossible to see as anything but retribution against the city’s predominantly African American population, Detroit is often viewed from afar as a cautionary tale, a post-industrial dystopia of vacant buildings and dormant factories.

The truth, however, is more complicated. On the brink of a new, post-bankruptcy beginning, Detroit is really two cities. One is comprised of wealthy enclaves like Palmer Woods linked to a compact, rapidly redeveloping downtown. The other is made up of the rest of the 139-square-mile urban expanse, populated by longtime residents who have fought for decades to survive in an environment that has become increasingly uninhabitable.

In the first Detroit, private security is common and the living is relatively safe. In the second, running water has systematically been cut off from at least 27,000 households this year alone, the latest in a series of government-enacted policies that have made daily life an increasingly desperate battle. Rather than growing closer in the coming post-bankruptcy era, many residents fear that these two Detroits— already so separate and unequal—will have increasingly divergent futures.

Prophecy Fulfilled

On November 7th, a federal judge approved the city of Detroit’s plan to exit the largest municipal bankruptcy in American history. That bankruptcy, the need for which was hotly contested by residents and leading economists, was only the latest in a series of controversial steps that included Governor Rick Snyder’s imposition of an unelected emergency manager to oversee the city’s finances.

After 16 months of wrangling, city and state officials expressed cautious optimism about the bankruptcy deal, which eliminates more than $7 billion in long-term city debt and includes cuts to the pensions of city workers, a violation of the state constitution. Creditors and insurance companies agreed to accept less than full repayment of the debts owed by the city, in some cases as little as 14 cents on the dollar. The plan also frees up $1.7 billion for Detroit to reinvest in essential city services like the fire department and the rebuilding of its system of streetlights.

The new debt readjustment plan is not, officials cautioned, the solution to all the city’s problems but at least they consider it a good start. For Wayne State law professor Peter Hammer, however, lurking in the bankruptcy plan is a potential future that’s far more sinister than anyone is advertising. As Hammer explained, Detroit has become a blueprint for the creation of a “self-acknowledged, self-defined second-class city,” one where the state guarantees only the most basic services to most of its inhabitants: “some police,” “some fire protection,” and “a bulldozer department” to raze abandoned houses, while the remaining essential services will be available only on a private basis for those who can pay.

That Detroit is a more than 80 percent African American metropolis makes the idea of its rise from bankruptcy with second-class status all the more problematic. As Hammer explains, the plan for Detroit bears an eerie back-to-the-future resemblance to the famed Kerner Commission report of 1968, issued by a presidentially appointed panel in the wake of the urban rebellions that were then sweeping the country. Its findings were that the nation was moving toward two societies: black and white, separate and unequal.

“That was viewed as a call to action, as unacceptable in 1968,” comments Hammer. Nearly a half-century later, he adds, it’s portrayed as progress. The vision of a future Detroit as a sprawling second-class black city with a small, wealthy downtown and a few elite neighborhoods surrounded by thriving white suburbs will, he projects, bring the 1968 finding to life. “The truth is, what [bankruptcy] Judge Rhodes will do when he approves the bankruptcy plan of adjustment is ratify that conclusion as prophecy.”

Uninhabitable

On a Friday in mid-October, the evening before two U.N. officials were to begin investigating whether Detroit’s mass water shutoffs constitute a violation of international human rights law, Marian Kramer was rushing around finishing up last-minute preparations. There were out-of-town guests to attend to, children who needed to be picked up from the YWCA, details to confirm for the following morning’s meeting with the lawyers.

Kramer, who has closely cropped gray hair and a stride like the snap of a rubber band, is one of the leaders of the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, a union of low-income people. She and co-organizer Maureen Taylor have been fighting water shutoffs since Highland Park, an independent city enclosed by Detroit, first began disconnecting water service in the 1990s. Hers is among a collection of groups— known as the People’s Water Board Coalition—that called on the United Nations to pay Detroit a visit.

As Kramer shuttled about in her minivan, she narrated the history of the streets rushing past. Detroit is, after all, a city best understood by driving past its steepled churches, past the barbecue joint that, back when the auto factories were still open, attracted lines around the block, past the cluster of people congregating with candles on a street corner, while all around them, dusk invades the space ceded by decommissioned streetlights.

“Someone got killed over here,” Kramer murmured, surveying the small vigil. “A three-year-old girl got shot the other night. Her momma was shot, her father was shot. I don’t know what it is. Every night, every morning, we wake up and there’s pure war here.”

As the city government has receded, a lack of services has made parts of Detroit all but uninhabitable. The injustices pile up: the threat that Child Protective Services will seize custody of children who are living in waterless homes; the streets upon streets of emptied houses, their roofs caving in, their porches collapsing, their bricks blackened by fire; the all-too-common violent deaths in neighborhoods without private security, where residents must rely on a decimated public police force that clocked an average response time of58 minutes in 2013; the charade of public school board meetings, where few decisions can be made because the school district is under the control of an unelected emergency manager the board has voted three times without success to fire; the death of a seven-year-old girl at the hands of a Detroit police officer wielding a submachine gun as his unit was being filmed executing home raids for an A&E reality TV show; the heartbreak of watching the city being disassembled and sold off as if at an estate sale—despite the fact that this Detroit has declared it will not die.

Tangela Harris, whose tap was turned off for 11 days last fall, explained that the worst insult wasn’t living with two young children in a house without water, but Detroit’s loss of control over a once-world-class water department, a stipulation of the bankruptcy adjustment plan. “There was pride in the water company,” she says. “The one piece of power that black people had in this city is now gone.”

Across this Detroit, the grief comes pouring out in town hall meetings and in the booths of diners (known locally as “Coney Islands”). Many here quietly wonder about the purposefulness of it all or, as one resident finally asked the U.N. officials during their visit: “Does this, all that you’ve heard, meet the legal definition of genocide?”

And yet, despite these injustices and the feeling of bitterness that go with them, each morning this Detroit, too, rises.

Point of Origin

Retired city construction inspector Cheryl LaBash rarely ventures downtown any longer. The last time she did, it was to protest what she sees happening to her city. We sit together in a small park called Campus Martius, which allocates about the same amount of square footage to a ritzy restaurant and a seasonal ice skating rink ($8 for adult admission, $7 for children) as to green space. LaBash has shoulder-length, white-streaked hair and wears a t-shirt that reads, “Hands Off My Pension.” She’s also carrying her old hardhat, just as a memento. She’d worn it during one of her final jobs with the city, supervising a team of construction workers as they tore up the ground right below where we were sitting.

The objective was to move Woodward Avenue, one of the city’s main thoroughfares, in order to clear the space to build Campus Martius. During the construction process, LaBash remembers discovering that the survey marker for southeast Michigan—the point of origin from which the entire region is measured—lay underneath the new park. That only strengthened her feeling that the transformation of this space from a main public thoroughfare into a privately administered park patrolled by corporately hired security guards was a symbol of the privatization that her city had undergone.

Today, the downtown section of Detroit hums with construction projects and is dotted with surprisingly expensive parking lots. Even as much of the rest of the city is neglected, it is being rapidly transformed. Most of this change is being driven by Dan Gilbert, the billionaire founder of Quicken Loans, one of the largest mortgage companies in the United States. In 2010, he moved the company’s headquarters from the suburb of Livonia, Michigan, to downtown Detroit and brought thousands of his employees into the city center with him.

Gilbert has also taken matters into his own hands when it comes to securing his rapidly expanding downtown empire. He’s organized his own 24/7 private security outfit, which patrols his approximately 60 buildings on foot, on bikes, and in cars. He’s also had hundreds of closed-circuit cameras installed in the area. Gilbert’s men monitor the feeds from those cameras (along with the social media accounts of residents and community groups) around the clock in the surveillance center in the basement of the Gilbert-owned Chase building.

“You feel like you’ve got into a deep room of the Pentagon,” says law professor Hammer on the surveillance room, which he recently toured with his students.

For new downtown residents, the rising levels of security and surveillance are considered a welcome—if sometimes perplexing—phenomenon. Patrick Klida, a young lawyer from the suburbs who moved downtown a few years ago, tells of an early morning call he received from Gilbert’s men last summer. His car, he was informed, was being broken into.

“The high-def cameras had found someone throwing a rock through the car window,” he explained. Within minutes, Gilbert’s security monitoring team had run the car’s plates, discovered that it was registered to his mother, located her number, called her at five in the morning, gotten his number, and called him.

To Cheryl LaBash, however, this new private security set-up isn’t just a byproduct of downtown gentrification; it’s yet another threat to Detroit’s crippled democratic process and the ability of its residents to express political dissent. Last February, private security guards stopped LaBash and a handful of other demonstrators from pamphleting and gathering petition signatures inside Campus Martius, which she believes is an encroachment of her First Amendment rights. The legality of the move may soon be contested, since Campus Martius is one of a number of Detroit parks that, while privately administered, is still officially publicly owned. As for why it seemed like the security guards were expecting the group of pamphleteers, one officer explained to LaBash, “a little birdie told us,” an apparent reference to the monitoring of activist Twitter accounts.

As LaBash sees it, the revitalization of the area isn’t part of an effort to revive “Detroit”; it’s a process meant to erase the city’s history and the vast majority of its people, including herself. She ponders the complicated ways in which such processes are so often driven by the few but executed by the many. Gesturing toward the park, she says ruefully, “And I was part of that change.”

Collisions

In a city of less than a million residents, the two Detroits nonetheless seem to collide at every turn.

The night before Halloween, known locally as Angel’s or Devil’s Night, the neighborhood association of East English Village, another of Detroit’s wealthy enclaves, hosted a potluck dinner and organized a volunteer resident security patrol. Setting vacant buildings afire on this night has become something of a grim yearly tradition in the city and a growing danger to neighborhoods that can’t afford their own privatized security forces. Although, unlike poorer areas of the city, this wealthy and well-organized community hasn’t suffered anything worse than a broken window on Devil’s night in years, it wasn’t taking any chances.

Around nine, as residents clustered in association president Bill Barlage’s driveway, drinking hot cocoa and eating chili and bacon-wrapped sweet potatoes, newly elected mayor Mike Duggan arrived.

“Does Joe Biden live here?” Duggan asked jokingly, provoking a wave of laughter.

The vice president had indeed visited Barlage’s home during a trip to Detroit on Labor Day weekend because, as Barlage put it, “The mayor wanted to show Biden a solid neighborhood.” In Barlage’s mind, the community’s success can be explained in part by its willingness to invest in private security, raise an active volunteer patrol, and generally keep its residents engaged and active. In addition, Barlage and the association promote continuing close relationships with both the city police department and the mayor’s office.

“We watch houses, we log houses,” he said.

A few blocks from his house, however, East English Village resident Andrew Cox has had quite a different experience in the neighborhood. For the last two years, he and his fiancée have been living in East English Village in the same way that thousands of poor residents elsewhere in the city have survived the economic turmoil: by occupying a vacant house, fixing it up and paying utilities. Like others in their situation, he and his fiancée were also putting a percentage of their monthly income into a bank account administered by a community group in order to collectively pay costs like property taxes.

A handsome thirty-something with a navy blue cabbie hat cocked at an angle on his head, he said he hadn’t found East English Village particularly welcoming. Earlier in the year, he explained, someone broke into the house and destroyed much of the kitchen, removing doors from their hinges and knocking out part of a wall. The break-in happened despite the community’s tight-knit watch group or perhaps— and this was his suspicion—because of it; because, that is, he and his partner didn’t fit the neighborhood’s profile and some members wanted to see them go.

Mostly, he was glad that the intruders hadn’t taken his great grandmother’s King James Bible, which the family had brought up from the South with them decades ago. In the wake of the break-in, he had received an eviction notice, which he wasn’t going to fight, since the state had recently enacted laws that made squatting a felony.

“I’m not going to jail just to have a roof over my head,” he said. “If they want the house so bad, they can have it.”

Back at Barlage’s place, the mayor was shaking hands and preparing to leave. “Well, looks like the neighborhood is safe,” Duggan declared to another round of laughter as he and his men strode down the driveway.

Eyes Don’t Cry

That Sunday evening, Marian Kramer’s weekend of work was almost over.

The town hall meeting for the visiting U.N. officials had ended after dozens of testimonies on what it meant to live without running water. Although there hadn’t been enough time for everyone to speak, people were now filing out of the atrium of a local community college, heading home to prepare for another week.

Some, however, were staying for the buffet of chicken, rice and beans, salad, steamed vegetables, and sheet cake. “Commander” Brown and his wife, also a security officer with Threat Management, were keeping a close eye on the two U.N. officials, accompanying them in line and even to the bathroom.

Finally, after the dinner was over and the guests had been thanked for investigating the water shutoffs, Stevie Wonder’s “My Eyes Don’t Cry” filled the large room. Dozens of people began heading for a corner that quickly became a makeshift dance floor. Soon, just about everyone fell into step: Maureen Taylor and the U.N. officials, out-of-towners and locals, a public school teacher, a school board member, and a man who had recently parked his wheelchair in the middle of a street to block the water trucks from heading out to turn off some more taps.

Despite the hours of testimonies over that weekend by residents living without water, by mothers fearful of losing their children and careful to conserve every drop of moisture —“I don’t cook rice, beans, anything that would cause evaporation,” explained one woman—a sense of joy and relief, mixed with the heady sweetness of chicken, pulsed through the crowd. One resident broke into a smile as she pivoted in her chair and surveyed the cluster of people calling out the steps and moving together, as if there were no kitchens without running water, no private surveillance cameras, no bankruptcy, no emergency manager, no emergencies at all—as if, for a moment, there were not two Detroits, separate and unequal, but just one city, hell-bent on survival.

“This is why they can’t kill us,” she said.

And these words summed up, perhaps more than anything else, the history of this side of Detroit—and whatever promise may lie in its future.

Link to original article from In These Times

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the

Imagine going to the polls on Election Day and discovering that your ballot could be collected and reviewed by the ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'

ACLU Blueprints Offer Vision to Cut US Incarceration Rate in Half by Prioritizing 'People Over Prisons'  "These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein

"These disasters drag into the light exactly who is already being thrown away," notes Naomi Klein  How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.

How about some good news? Kansas Democratic Representative advances bill for Native Peoples.  What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on

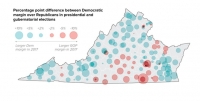

What mattered was that he showed up — that he put himself in front of the people whose opinions on On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto

On a night of Democratic victories, one of the most significant wins came in Virginia, where the party held onto A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in

A seismic political battle that could send shockwaves all the way to the White House was launched last week in In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen

In an interview with Reuters conducted a month after he took office, Donald Trump asserted that the U.S. had “fallen Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed

Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the sweeping criminal charging policy of former attorney general Eric H. Holder Jr. and directed